This page is also available in / Cette page est également disponible en:

![]() Francais (French)

Francais (French)

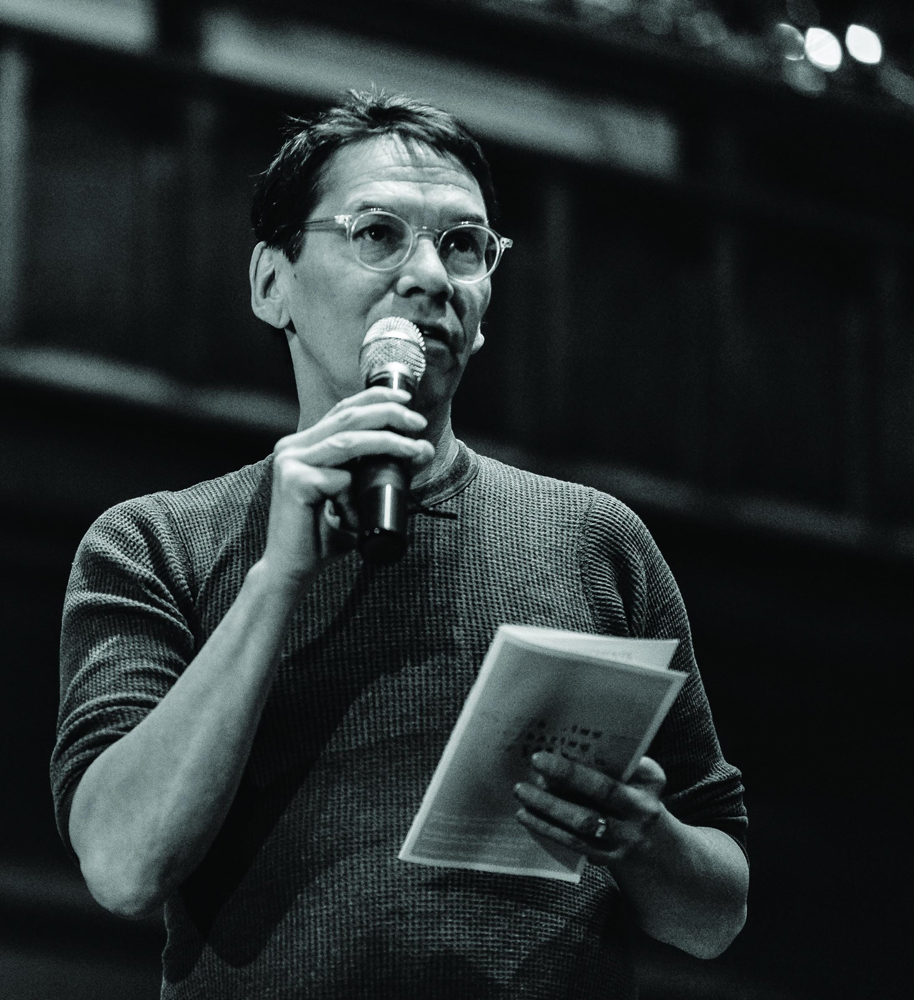

Medicine is an important element of composer Andrew Balfour’s creative pursuits. “People think of music as a refuge, but music can also be a powerful entry point to healing,” he says.

The notion of healing is one close to the Cree composer’s heart. His work is characterized by the combination of polyphony and Indigenous themes related to history and identity. He skilfully pokes holes in the Eurocentric narrative of classical music even as he uses its foundations to explore serious issues. Such a creative instinct has painful roots.

As an infant, Balfour was taken away from his Cree mother as part of the Sixties Scoop, a term referencing a time in Canadian history when Indigenous children were forcibly separated from their families into the child welfare system, largely without the consent of their families or bands. Over the span of three decades, more than 20,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children were removed by child welfare authorities and placed for adoption in mainly non-Indigenous households. According to a report from Indigenous Foundations (an information resource run by the University of British Columbia), these children eventually experienced both emotional and psychological problems as a result of cultural suppression.

Though Balfour was raised by a music-loving family with Scottish roots—his adoptive father was an Anglican minister and a trombonist, his adoptive mother a violist—he struggled with attention-deficit disorder in school, dropped out of Brandon University after a year, and eventually lived on the streets of Winnipeg before serving a four-month sentence at Manitoba’s Milner Ridge Correctional Centre in 1995. During that time, Balfour met numerous First Nations and Métis inmates. “They accepted me like a brother,” he told The Globe and Mail in 2019. As a result of those meetings, Balfour embraced his Cree heritage and decided to use music as a vehicle for both its exploration and expression.

Photo: Kristen Sawatzky

In 1996, he founded the Winnipeg, Manitoba based vocal group Camerata Nova (now Dead of Winter) and the rest would be history—but Balfour has made it a mission to re-examine history through a distinctly Indigenous lens. Ambe, his first published work, uses Ojibwa text and a persistent bassline reflecting the sounds of a ceremonial drum. The music-drama Take the Indian, commissioned by the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra for the 2015 New Music Festival, refers to the official intention of residential schools to “take the Indian out of the child” and is based on Balfour’s direct observations from attending Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings. His choral, instrumental, and orchestral pieces often integrate an array of sounds, styles, genres, and artistic disciplines, with Empire Étrange: The Death of Louis Riel, Migiis: A Whiteshell Soundscape, Manitou Sky, Bawajigaywin, Wa Wa Tey Wak (Northern Lights), and Mishabooz’s Realm (commissioned by L’Atelier Lyrique de l’Opéra de Montréal and Highlands Opera Studio) being a small sample of his creative output.

“Music as pure entertainment is one thing, but music as a story and a message is so important,” Balfour says. “These stories need to be told, and the only way I know how to do it is with music.” The award-winning composer has written commissions for a number of prestigious outlets, including the Winnipeg, Regina and Toronto Symphony Orchestras, Tafelmusik, Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, and the Vancouver Chamber Choir.

Complementing his compositional pursuits is Balfour’s passion for education and outreach. He has been involved in initiatives on reserves and in urban schools for over a decade, and knows first-hand the power of having access to music education. He grew up with three full-time music teachers at his own school, plus various bands and choirs active during the year. “You can see the effects on the students when they don’t have the opportunity to sing or play an instrument—when they don’t have the chance to be in a collective with others,” he notes. “So now it’s really important to get kids to sing, and the power of them singing in an Indigenous language is incredible. It gives them hope, and that’s very powerful.”

Just as powerful was the “reset” he says the coronavirus pandemic forced in terms of Indigenous issues and their presentation within the Canadian arts scene. “Since conductors and musicians weren’t practising or programming concerts, there was a lot of downtime, which led to discussions around decolonizing music, diversifying music, about reaching wider audiences, making choral music more accessible for the wider public. I certainly feel that what we got out of that time, on the positive side, were really important conversations that will continue, for a long time.”

Does he think European composers should be wiped off programs in Canada? Not quite. “When I say I want to decolonize music, that doesn’t mean I want to get rid of Beethoven or Mahler,” Balfour says, “but what I want to see, or help to be part of, is music which is accessible to all people.” The human voice is a quick route to that accessibility. “I like the sound of the human voice, I like putting harmonies together, and I like telling stories, sometimes hard stories, through that medium because it’s a way I think people really understand.”

Notinikew, his anti-war mini-opera, provides such immediacy, exploring the experience of war from an Indigenous perspective. A multimovement work for choir and cello featuring narration, the work—which uses the Cree word for “going to war”—was created to mark the 100-year anniversary of the end of the First World War in 2018. It will be presented in Montreal on Feb. 24 as part of biennial festival Montréal / Nouvelles Musiques (MNM), which, this year, marks the 57th anniversary of the Société de musique contemporaine du Québec (SMCQ).

Balfour, a self-confessed history buff, was fascinated by stories of Indigenous soldiers who volunteered to be part of the First World War. “My question was always: ‘Why? Why go fight in a white man’s war?’” He subsequently learned that many Indigenous people believed their efforts would lead to a better life. “They didn’t,” Balfour says bluntly. “They were forced to go back to the reserve, where they were shunned by their own communities. It is one of the saddest stories I know in this country’s history.” The work disrupts traditional ideas of Remembrance Day and its observance. “People think it is just the poppy and the flags and the playing of the Last Post,” he says, “but Notinikew forces us to think about the Indigenous people who sacrificed a lot for very little. Everybody talks about how they fought for freedom and rights, but what kind of rights do you have when you come back to a country that locks you up in a little piece of land and won’t let you speak your language or celebrate your culture? That’s not freedom, to my mind.”

Also touring is Nagamo, the project Balfour did with Vancouver-based vocal group musica intima in 2022. The word “nagamo” means “sings” in Ojibwa, a subtle title for a powerful work. Released last year through Redshift Records, the album is a stirring reimagining of the choral works of Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, and Orlando Gibbons, with the original sacred Latin texts reworked by Balfour into Ojibwa or Cree; they are, very purposely, not direct translations. He writes in the album’s liner notes that the combination of texts and music here allows for “a more Indigenous perspective of spirituality” even as the beauty of the polyphony is maintained. Considering the painful role of the church in Indigenous history, the album facilitates a healing that is as much sonic as spiritual. “I don’t hate the church service music,” he told CBC Radio in 2022; “I wouldn’t be here without learning music through being a choir boy—I guess this is a personal reconciliation with myself and non-Indigenous institutions.” CBC Music selected Nagamo as one of their “22 favourite Canadian classical albums of 2022” in December. Balfour, together with musica intima, will be touring Nagamo in March, with stops in Toronto, London, St. John’s, Winnipeg, and Edmonton.

Bigger projects with major Canadian arts institutions must, he says, be based on ”100 percent trust and understanding” and must include Indigenous talent. “If it’s only a commission, and then you hand complete artistic control over to the organization—no. I would want to ensure it’s Indigenous run, led, and produced. That’s the only way it’s going to work.” Who would he love to work with? “I have my eyes on projects with other Indigenous creators, like setting text by Tomson Highway,” he says with a smile, referencing the famed Indigenous writer. “But, of course, it would have to be the right climate.”

Current creative satisfaction is tempered by reality. “I’m a happy person where I am as a composer. I’ve never been busier,” he admits, “although I am not happy with the state of Indigenous people in this country. I’m not a doctor, I’m not a lawyer, I’m not a politician—I am a storyteller, and that’s a really powerful thing.”

Notinikew, MNM Festival, Maison symphonique, Feb. 24.

www.smcq.qc.caNagamo is touring Canada:

• Toronto: March 5, 2023

• London: March 7

• St. John’s: March 11

• Winnipeg: March 15

• Edmonton: March 18

This page is also available in / Cette page est également disponible en:

![]() Francais (French)

Francais (French)