This page is also available in / Cette page est également disponible en:

![]() Francais (French)

Francais (French)

The magic of The Little Prince, Antoine de Saint Exupéry’s classic children’s story, can be largely ascribed to the synesthetic nature of the work itself. The interrelationship of visual and narrative art is at the heart of this story; when a pilot stranded in the Sahara Desert encounters a tiny prince, the prince asks him to draw a sheep to eat the baobabs on his planet.

On Nov. 17, Orchestre Métropolitain’s adaptation of The Little Prince for live actors and orchestra sought to add yet another artistic element to this synesthetic work: music. This was a very ambitious project. On the one hand, the written story, with its overlapping visual and narrative elements, had to be set for stage. On the other, its synesthetic qualities were intensified even further by the addition of music.

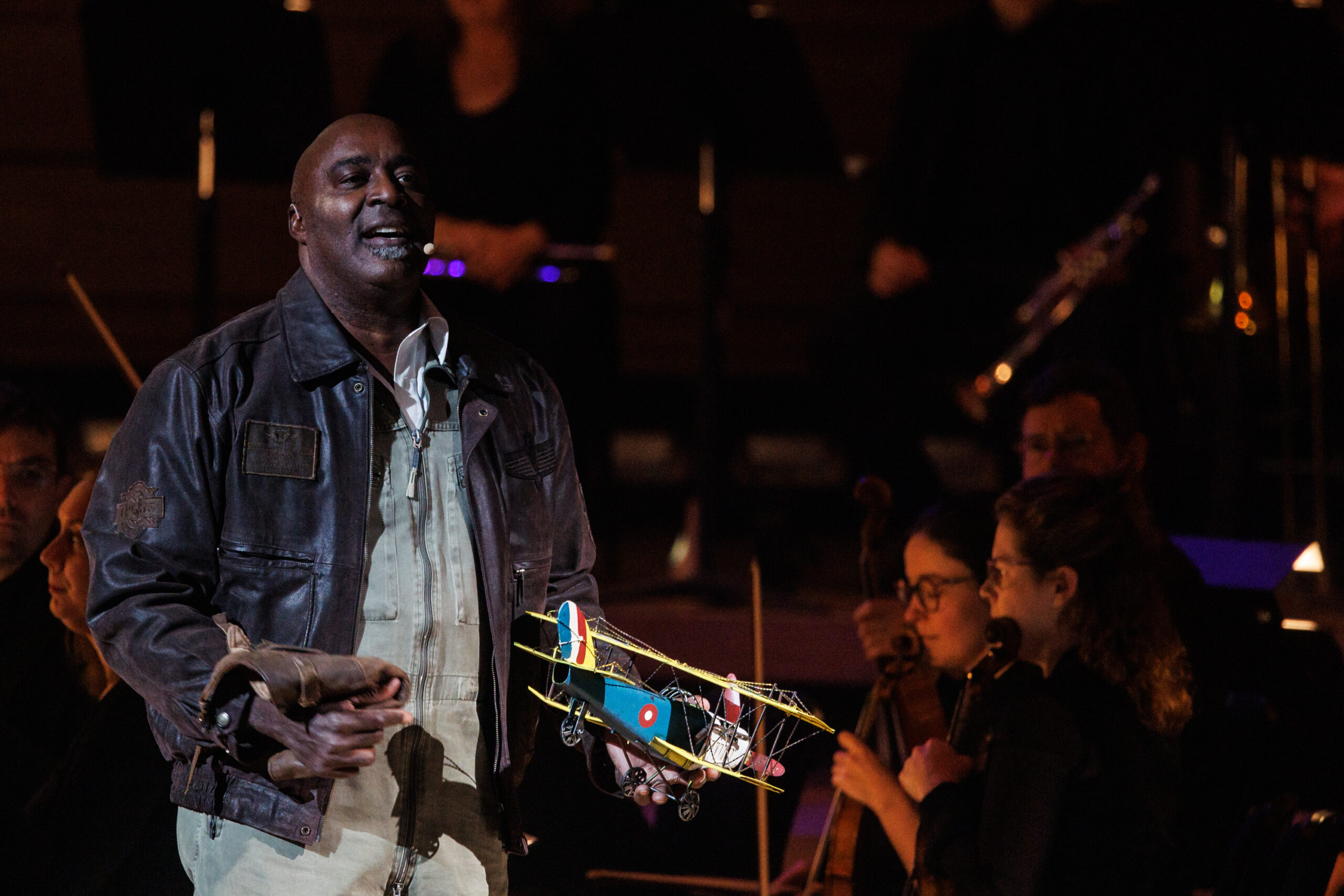

Widemir Normil as the pilot. Photo: Denis Roberge

What you missed:

Most of the performative aspects—the acting, staging, and musical performances—were very well accomplished. Each actor carried the script, which was taken almost entirely from the original work, superbly. The actors’ interactions with the audience were particularly delightful for children. The drunkard’s meandering entrance on stage, while addressing the front row in a semi-improvised manner, was particularly hilarious.

Though the costumes and set were modest, they were very effective. Like the script, the onstage drawings were taken directly from Saint-Exupéry’s book—its narrative and illustrations contain a marvelous childlike simplicity. Frédéric Bélanger’s staging did not only preserve the wonderful simplicity of Saint-Exupery’s work but enlivened it. He accomplished this not with flashy lights or grandiose gestures on the part of the actors, but with an authentic visual palette and a dynamic use of the actors’ on-stage placement—from high up in the balcony to right in the middle of the orchestra. Éric Champagne’s compositions had several strengths: the orchestration was well-wrought, and the celestial, Holst-like melodies aptly conveyed the spatial theme of the work. Particularly striking moments were the snake’s rattling entrance to maracas, and the wind gusts of the woodwinds and percussion.

Orchestre Métropolitain directed by Thomas Le Duc-Moreau Photo: Denis Roberge

Gripes:

Unlike the production’s visual elements, the music did little to advance the narrative. It seems like Champagne intended his music to serve a mainly descriptive role.

In general, the musical numbers lacked catchy hooks that the audience could consistently associate with elements in the narrative. There was little that was memorable about this music, and it was generally reminiscent of a run-of-the-mill movie soundtrack. There was also little interaction between the actors and the music itself. Since the music did not serve a clear purpose, I found myself wondering throughout: “Why have an orchestra at all?”

I was relieved to learn that Champagne did not originally compose this work for orchestra but for woodwind quintet. When it premiered in Switzerland by Ensemble Zeferino, the work was performed by actor/musicians. There was a much greater overlap between the script itself and the accompanying music.

A full orchestra is an enchanting sight, especially for a young child. Yet just because something is big and beautiful does not make it the right fit. A smaller musical ensemble seems more adapted to a work in which the music plays a minor part. The performance also suffered from numerous technical difficulties with the lighting. Together with the music-related problems, this Little Prince served as an example of how artistic merit is not necessarily enhanced—and can even be hindered—by a big, flashy production.

Upcoming performances by the Orchestre Métropolitain include Eternal Orlando in late November and Holiday Melodies in early December. www.orchestremetropolitain.com

This page is also available in / Cette page est également disponible en:

![]() Francais (French)

Francais (French)