This page is also available in / Cette page est également disponible en:

![]() Francais (French)

Francais (French)

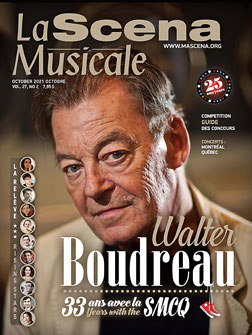

A major page is about to turn. The Société de musique contemporaine du Québec (SMCQ) in September announced the retirement of its artistic director Walter Boudreau. “The challenges ahead for the SMCQ, as well as for music and the arts in the post-pandemic world, will be unprecedented, demanding and exhilarating,” Anik Schooner, chairman of the board of the new-music society, said in a statement. “That’s why I think it’s the right time to pass the torch.”

33

Eager to ensure a smooth transition, this man with no inhibitions and a head brimming with ideas had already informed the board, near the beginning of a four-year plan, of his desire to step down and devote himself fully to composition. Artistic director since 1988, Boudreau succeeded Gilles Tremblay (1986-1988) and notably Serge Garant (1966-1986), co-founder of the SMCQ, two composers of contemporary music like himself and two of his professors at the Conservatoire and the Université de Montréal.

“I joined the SMCQ in dramatic circumstances because Serge Garant died suddenly from cancer,” Boudreau says. “I was the ideal person to take over at this point. I had conducted the SMCQ, studied with Garant and knew everyone. Even though I have a difficult personality, the musicians wanted to work with me.”

Thirty-three years of musical creativity have thus elapsed under his leadership and countless achievements can be attributed to the SMCQ. In recent years, several of his pieces have been premiered or performed as part of the Montréal/Nouvelles Musiques festival, notably Chaleurs (1989) by the saxophone quartet Quasar during the 2021 edition. But we must go back to Solaris (2014) and the Concerto de l’Asile (2012), commissioned by pianist Alain Lefèvre, to find Boudreau’s other latest creations.

Given his double duty as artistic director and conductor, he could no longer find little time to compose. “Quietly, the seed of some frustration germinated in my mind. I was like a camel in the desert that was at its limit. I am 73 years old. In my head I’m 19, but my body and my ability to work are not getting any younger. In 10 years, I’ll be 83. Fortunately, my mind is intact. I want to use it as much as possible now to compose.”

The idea of leaving after 33 years of loyal service also appealed to him. A nod to his poet friend Raôul Duguay, whom he had met at Expo 67, and to the number 3, which was the favourite number of their group Infonie (1967-1974). It was during this time that Boudreau, then working as a jazzman, took his first steps in composition and set out to meet composers who, for many students of his age, were major thinkers.

Musical meetings

Having first studied the saxophone with Douglas Michaud at Arthur Romano’s studio in Montreal from 1960 to 1965, Boudreau in 1968 began his training in composition with Bruce Mather at the Faculty of Music of McGill University. From 1970 to 1973, he studied at the Conservatoire de musique de Montréal with Tremblay and at the Faculty of Music at the Université de Montréal with Garant.

A series of courses followed with composers whose names make the head spin: Olivier Messiaen in 1971 at the Conservatoire national de musique de Paris, Pierre Boulez the same year at Kent State University (Ohio), then Karlheinz Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis, Mauricio Kagel and György Ligeti the following year in Darmstadt, Germany, an emblematic place for contemporary music in the aftermath of the Second World War. In 1973, Boudreau sought out Xenakis in Paris for another training course in composition.

“All of these people were reputable in my view, people whom I visited and learned from,” Boudreau says. “I certainly did not adopt the religious devotion of Olivier Messiaen but I did appreciate his incredible ability to harmonize a cantus firmus and imbue it with colour. I appreciate the music of Pierre Boulez. I have conducted it a lot, but I’m not particularly a fan (I’m more of a fan of Louis Andriessen).

“What I retained from Boulez was his style as a conductor. I spent a summer with him at Kent State. This is where I got a lot of experience just watching him work. How to approach a score, a rehearsal. Do not lose patience when things are not to our liking because it will come with experience and more rehearsal. He wasn’t the warmest person in the world, but he was far from a cold man, he had a good sense of humour and a great way of working. With Xenakis it was structural madness pushed to the limit. What I remember most are the conversations I had with him. We were discussing music, structure – in short, whatever I felt like.”

Starting at the SMCQ

At his very first concert as conductor at the SMCQ, on Nov. 9, 1972, Boudreau did not perform in tails. He put on his red “infonic” gown, with a large yin-and-yang symbol on front, a white tuque inscribed with the number 33, and big red slippers. Dark suits were not for him! They remind him of the funeral home in Sorel, where he lived as a child, and of the people dressed this way who preceded the funeral processions. “I find this dismal as can be,” he said.

From this “infonic era,” Boudreau has retained, among other things, the colour red – his favourite – which he now sports with his legendary Converse sneakers. A few years earlier, before he landed his first contract as a conductor, Boudreau had bumped into Garant on St. Catherine Street, at noon, between rehearsals with his jazz quartet. His colleague, the pianist Pierre Leduc, introduced them. “He’s a genius, he writes incredible music,” Leduc then confided to Boudreau who, at first glance, had judged the composer to be “a funny fellow with big glasses and big sideburns.”

“Who would have thought, at that moment, that I would become not only a student but a friend of Serge Garant and one day would take his place as artistic director?”

After this chance meeting, Boudreau, encouraged by his new friend Raôul Duguay, saw Garant conduct at Salle Claude-Champagne. On the program of this concert of April 25, 1968 was Déserts by Edgard Varèse, a composer whose music Boudreau already loved. “There he was. I saw him working as a conductor, I saw the SMCQ ensemble… It changed my life. On several occasions since I have conducted Déserts, his last work … It blew me away.”

Projects great and small

After accepting the artistic direction of the SMCQ, Boudreau cultivated projects of various dimensions. “The Symphonie du Millénaire, no one has been able to beat this,” he says. It was indeed hard to beat: in a single evening in June 2000, a 90-minute mega-symphony, written collectively by 19 composers, performed by 333 musicians with the digitized sound of 15 bell towers, 15 ensembles, a large organ, a carillon of 56 bells and two fire trucks spread over the site of St. Joseph’s Oratory.

After accepting the artistic direction of the SMCQ, Boudreau cultivated projects of various dimensions. “The Symphonie du Millénaire, no one has been able to beat this,” he says. It was indeed hard to beat: in a single evening in June 2000, a 90-minute mega-symphony, written collectively by 19 composers, performed by 333 musicians with the digitized sound of 15 bell towers, 15 ensembles, a large organ, a carillon of 56 bells and two fire trucks spread over the site of St. Joseph’s Oratory.

Rather than draw attention to this event or that, Boudreau prefers to talk about the three main axes around which so many of his projects turn. First, SMCQ programming for young people, “because the future resides in youth”; then, the Hommage series, “because it brings a composer into society”; and finally, the MNM festival, “because there was so such thing.” This festival, Boudreau stresses, is what made it possible for the SMCQ to measure up to its international counterparts. “Whether micro or macroscopic, I am proud of everything I have achieved.”

Looking ahead

Soon Boudreau will be able to return at last to the things he had to put aside during his tenure at the SMCQ. “I’m cleaning up my scores,” he says. “I never had time to finish all the corrections. I’ve always composed between two tours, between two concerts, between two trips. I’ve always worked in shaky circumstances, but still wrote some damned good music. Now I will be able to work with a little more peace of mind.”

For a year now, Boudreau has been making final corrections to Golgot(h)a, a work composed in 1990 and included on the recording Walter’s Freak House (ATMA, 1991). This piece is already slated to be performed at the opening concert of the 2023 MNM festival, whose theme will be “music and spirituality.” If health conditions are right at that time, Boudreau will return as a freelance conductor to oversee his music.

Boudreau also has a major musical project in mind for the City of Montreal. He would like to submit the idea to the new or reelected mayor. “I am waiting to meet the person in question. It’s a huge project. It will take a few years of work.”

This is not all. He is planning an autobiography in which he can hold forth at length on the many stories, big and small, that make up his life.

While waiting for this volume, Boudreau is pleased to see a history of the SMCQ released as a series of podcasts. “Even if Réjean Beaucage has written a wonderful book on the subject, not everyone has it at their bedside.”

Take note that Boudreau will remain in office until the SMCQ has completed the selection process and designated his successor.

This page is also available in / Cette page est également disponible en:

![]() Francais (French)

Francais (French)