Emmanuel Vukovich: “Resilience has been most frequently defined as positive adaptation despite adversity. Recently, however, research has begun to recognize that much of what seems to promote resilience originates outside of the individual. This has led to a search for resilience factors at the individual, family, community, and most recently, cultural levels.”

LSM (VL): This is an interview with violinist Emmanuel Vukovich for La Scena Musicale. So, Emmanuel, tell us a little bit about your background. In our telephone conversation, I understood that we have a shared cultural background.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yes, Viktor, thank you. Thank you very much for coming to my place.

LSM (VL): Thank you for having me.

[00:50] Emmanuel Vukovich: My background: My father is Croatian; he was born in a small town in Lika, Ličan. I was born in Canada. My mother is German; she was born in East Germany. I grew up in Western Canada, Calgary. Never really learned the language, but I’m getting there. So anyways, I was excited when I saw your name, and then we spoke on the phone, and you told me you’re Serbian. So here we are in the new world, retracing our roots through music.

[01:27] My father played the accordion, not very well, but he would sing Croatian songs. I think that’s the strongest memory that I will always carry from him. He passed away about two years ago, so he’s no longer with us. This project has been… he passed away two months before I recorded this album. His presence has been very strong throughout the whole journey of creating this. [01:59] I would say, in many ways, this project is very biographical or autobiographical. It’s been a search for who I am. I remember going with my father the first time to Croatia, to these little villages, eating lamb, and spending three days together talking. They still cut hay by hand and put it on poles. […] It was very simple, but it impacted me profoundly.

LSM (VL): That close relationship with nature is one of the central themes of your album Resilience, and of course, the Eastern European, Balkan musical groups through your exploration of the work of Béla Bartok. You did your doctoral thesis on Bartók, could you maybe tell me about that?

Emmanuel Vukovich: Happily, very yeah. It’s interesting. Until my doctorate, most of the repertoire I played was Baroque, classical, early romantic. I had done very little contemporary music, meaning 20th-century. I really hadn’t touched much. The piece that I played a lot was the Solo Bach Partitas, especially the Chaconne, which I played everywhere imaginable.

And then I discovered this Bartok Solo Sonata, and I was like: I must play this. I’ve talked to many violinists, and they all told me they tried and failed. […] It’s not virtuosically that hard; it’s that everything blurs harmonically. It’s very difficult to listen to and it pushes the capacity, the boundaries, or the possibilities on the instrument to nearly impossible. It’s questionable whether the piece ever works in a sense. But I wanted that challenge and took it on.

Part of a doctorate involves research, analysis, and historical research. One of the first pieces I played as a child was Romanian folk dances. We all know Bartok was one of the pioneers of ethnomusicology, collecting folk songs to inform his language. Most of us know that. I assumed there were a couple of hundred pages of manuscript somewhere, maybe some folk songs collected, but when I started researching seriously, I realized it’s much bigger than that. Not many people I know are aware of that.

Colleagues and teachers were supportive, especially my teachers at Stony Brook, the Emerson String Quartet – Philip Setzer, and Eugene Drucker. They became known through their recording of the Bartok quartets and were the first to record and to perform all six in one cycle. They won their first Grammy for that. I had a talk with Phil. and he said, you know, you should really pursue this. So I went to Columbia where most of the manuscripts of this folk music collection were, where Bartok spent the last five years of his life.

A colleague of mine, she’s also from Calgary with Eastern European roots, Zosha di Castri, a Canadian composer. I talked to her, and he said she would put me in touch with the head librarian in charge of the archive collection. […]

I made an appointment with Jennifer Lee, who’s now retired. She showed me into this room with boxes and boxes of original manuscripts. This was digitized for the first time for my research. Because of copyright law, music doesn’t become public domain until 70 or 75 years after the composer’s death. I showed up in 2021, and as of 2020, it was officially in the public domain.

The quantity is staggering. There are tabulators where Bartok analyzes the syllables, the pitch range, rhythmic structure of each song. He believed this to be his most important contribution, more than the pieces he wrote. Through my research, I understand his intention.

At the same time when Bartok and Kodaly started recording folk melodies in Hungary and Romania, Arnold Schoenberg was developing the 12-tone system in Vienna. Schoenberg has been quoted saying the 12-tone system would ensure German supremacy of music for the next 100 years. There was an attempt to build the future of atonal music within the German or Central European tradition.

LSM (VL): However, there are other elements; the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time was highly diverse. So, Central Europe had a lot of varied elements.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Well, yeah, and also, you know, the Germanic tradition was very much in the kind of cerebral, analytical, theoretical framework. And the result was something that worked beautifully theoretically and mathematically. The question is, does it really work musically? And I mean, there are great pieces that were written with this system. But I think what Bartok was searching for was a door for what we now call atonal music, but out of the tradition of musical heritage from the people and from outside of Germanic academic [circles].

And what he discovered, really by mistake, is that many of these folk melodies are polymodal, meaning they have major and minor coexisting within the same measure, within the same phrase, that there is less of a clear tonic-dominant relationship per se. Because this music predates Bach. It predates Baroque. It predates the Renaissance.

LSM (VL): In a way, it’s looking for the origins of indo-european music, if one can say it that way.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yeah, yeah, exactly. And so what’s very interesting is then Bartok and Kodaly are working – and there were poets, and there was a whole Hungarian movement – and they inspired a professor at Harvard by the name of Millman Perry. And Millman Perry was a professor of oral literature at Harvard, specifically classic, Ancient Greek oral literature, and his question was how do people remember? How did oral tradition get passed down? Meaning, how did the Iliad and the Odyssey, how did Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey? How did people remember, you know such a scope? How did people remember and pass down verbatim these stories, these poems? It’s often rhyming couplets, they’re very strict form.

And so, he then went in 1930 to 1933, two major trips with Albert Lord, his assistant from Harvard. To what is, you know, former Yugoslavia (Serbia, Croatia) to villages where people were still illiterate, meaning there was no reading or writing. And he asked them, “do you know these long, heroic, epic poems”. And he recorded several hundred thousand reels that were on aluminum wax cylinder and then aluminum cylinder discs. And what he discovered is that no one recites these poems. They all sing them. It’s all song or 90% of it is song. And that melody and poetry or melody and the word have not yet separated. You know it’s really in Bach’s time, I mean, Gregorian chant, let’s say, where once you have melody being written down, that word and sound become two separate entities in our consciousness.

LSM (VL): Which developed with the growth of literacy.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yeah, of course. We have a concept of a word that’s independent of the sound of… Then in 1940, Columbia hired and brought Bartok to America and, for five years, he was hired. His contract was semester by semester. It was awful. He died poor. He was sick. But he spent the last five years transcribing all of this recorded material, both some of his own that he had done, but principally it was all these field recordings that Millman Perry had recorded that brought back to Harvard. […] The recordings are now at Harvard, he came and lectured at Harvard, but he spent his day basically transcribing melody after melody, song after song, poem after poem, of these recordings and [17:30] they have been sitting, collecting dust, so to speak. So, when I reflect on it, it’s interesting – my experience in farming… I remember rediscovering an old plow in the field – covered in rust and weathered. We took the time to grind it, sand it, and with an electric grinder, repaint it, stain it, and put new wooden handles on it before hitching it up to the horse. This process was reminiscent of discovering ancient manuscripts for me, a similar experience. You come across something old that’s been neglected or rejected, and, yeah, I would say it resonates. I firmly believe that what Bartok initiated is more of a beginning rather than a completed exploration. The language he delved into, through this folk material and folk songs, holds significant potential. I see it as an essential key to the future of music. Basically, I believe that’s a crucial aspect, put simply.

LSM (VL): If I understand you correctly, do you think there might be more enduring value in that source compared to a more theoretical process?

Emmanuel Vukovich: I believe so. It’s always a combination; it’s never solely one or the other. Another thing that happened during my doctoral studies involved a seminar on timbre. Stephen McAdams here at McGill emphasizes timbre as the new frontier in music. This seminar was enlightening. We listened to music ranging from the early Renaissance to Ligety. Then, we would visually represent what we heard on paper and engage in discussions. The central question was whether we could develop a language, a formal compositional notation for timbre, akin to what we have for pitch, rhythm, and harmony. We possess a language for the three primary elements in music. The question is, can we now develop a formal language for timbre or the quality of sound? Oral tradition, in essence, embodies that. It passes down through the experience of sound.

LSM (VL): I understand, through the experience of timbre. Specifically, human generated timbre.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yes, indeed. Instruments contribute as well, but mostly it’s the human voice. Many of these compositions are instrumental. What I have is only a very small part of it, but these are all instrumental melodies. Feel free to explore.

LSM (VL): Transcribed by Bartók.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Interestingly, upon closer inspection, you’ll find quarter tones and ornamentation. There are instances where he attempts to notate vibrato and thrills. Some are even arranged with other…

LSM (VL): He’s trying to emulate timbral characteristics through traditional music writing.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Exactly, yes. But that was really his question. That’s my question too. If someone did this today, these melodies, up until then, had never been written down by anyone. Why he chose two-four time, why did he select this key…

LSM (VL): He’s chosen to formalize oral tradition in a way that perhaps the originators of that tradition may not have considered.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yes, indeed. I think the first question on the table is: can oral tradition ever be formalized? Should it ever be formalized? Who knows? But I think what can be answered is how oral tradition can inform the future evolution of music?

So now let’s turn our attention to Sheila Silver and Gubaidulina, living composers with whom I’ve been collaborating. or Zosha’s music – her focus is predominantly on timbre. She composed a piece for this album titled “Patina” for solo violin, dedicated to her teacher Fred Lerdahl. The composition revolves around timbre, presenting a Caprice whose virtuosity lies not in fast or numerous notes, but in expressive [timbre]nuances. She employs squiggly lines in her formal language, often representing harmonics or half-harmonics. For instance, at the very end of the piece, the notes reach a very high pitch, which I’ll demonstrate shortly. Zosha serves as a prime example of a contemporary composer exploring new sounds and modes of expression. I won’t claim these are new feelings, as I believe human emotions are fundamentally timeless and universal. It’s about discovering a new language to convey these emotions. I think the more we explore… To sum it up, the danger in relying on an algorithm as a reference, is that it may eventually lose its human essence.

LSM (VL): Limits in a certain sense, the nuances of what we can express, and a certain instinctual, intuitive, perhaps direct mode of creativity.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yeah, the question is how much does it actually speak to our humanity. I guess because it’s actually speaking to, or if you understand?

LSM (VL): To a conceptual, intellectual aspect of humanity. It is a part of who we are. But perhaps, if I’m understanding you correctly, it may not express the full breadth of what we’re capable of. It may not touch the more heartfelt, intuitive, expressive potential that we can have. I feel that in your booklet for the album “Resilience,” you speak with a great amount of detail, passion, and a lot of thought about the human connection with nature, with each other, and with the environment. You refer to Bartók as a great synthesizer. Maybe you can tell us a little bit about how the contemporary composers, the three composers that you have brought into this, how would they fit into, you know, this concept?

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yep, yep. Well, I think all three of them would tell you that Bartok has been a major inspiration and influence in their lives. I’ll start with this image from the album booklet called “Resilience Micmac worldview or Micmac Universe.” It’s by First Nations Micmac artist Teresa Marshall. This is the original, as you can see. Yeah, you’ll have a picture, and it basically describes the four elements – earth, water, air, fire. It describes the Micmac cosmology.

LSM (VL): There’s symbolism woven in it…

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yes. I’m going to start with Sheila Silver, whose work “Resilient Earth Caprices” was written for me, but we collaborated on it extensively. It was a pandemic project. Sheila was a professor of composition at Stony Brook. She’s retired now but she was my thesis advisor.

When the pandemic hit, she decided to write me some solo caprices. There are four of them, and they relate to the four elements of nature, inspired by and describing the human-nature relationship. The first one is called “The Chipmunks and the Owl.” It’s a humorous piece about an owl catching a chipmunk. The second one is “Stillness by the Pond,” connecting earth and water. During the pandemic, Sheila acquired a beautiful property in Upstate New York with a pond in front of her house. In the mornings, she would watch the mist rise over the pond. We explored timbral and extended techniques, reaching high up on the instrument. The third one is “Teeming for Life,” capturing the activity and movement of energy found in every square inch of the soil, air, and around the pond where she would observe various animals, insects, dragonflies, mosquitoes. The fourth one represents fire and is titled “The Lost Nigun”. It draws from Sheila’s Jewish tradition, inspired by a prayer given to her by her rabbi many years ago. It‘s a meditation or variations on this Nigun. That’s “resilient Earth”.

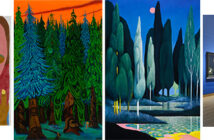

I’ll add that the album booklet also includes images by Mary Frank, a close friend of Sheila’s and a renowned artist who exhibited worldwide. We can incorporate images into [the article].

LSM (VL): Of course, we can add that, definitely.

Emmanuel Vukovich: We did the world premiere performance of “Resilient Earth” at New Paltz University, Samuel Dorsky Museum, and we performed the works with projections of these paintings behind me as I was performing. The second composer, [30:25] Dinuk Wijeratne, we met at Juilliard as students. He is from Sri Lanka but is Canadian. He came with his family, initially in London, then moved to New York. He was studying with John Corigliano while I was studying with Dorothy Delay. He wrote a Sonata for violin and piano, which, according to Dinuk, is his first composition where he incorporates the musical tradition of North Indian classical music, with which he grew up, with Western tradition.

The second movement, “Flautist on a Rock,” is an improvisation in that style. Hindustani music is a classical tradition like Western has its own classical tradition, and it has distinct colors, timbres, and textures, particularly associated with instruments like the bansuri flutes and the sitar. […] The bansuri flute, in particular, has a unique sound with ornamentation and improvisation that is very vocal, resembling human-like qualities.

LSM (VL): Melismas…

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yeah. But it’s interesting because Dinuk’s journey was really from East to West. Sheila Silver just completed an opera that premiered exactly a year ago, titled “1000 Splendid Suns,” set in Afghanistan. She has studied Hindustani music with a master in India for the last 10 or 15 years. So, her journey was from Seattle, from the West to the East. Bartok’s perspective is fascinating. Bartok believed in a common human ancestry and roots. He shared many letters with Yehudi Menuhin, for whom the Solo Sonata was commissioned and composed, where he writes about the common human ancestry and roots, emphasizing that the journey of music has been from the East to the West and from the South to the North.

LSM (VL): Dinuk is exploring some of these themes or topics in his work, would you say?

Emmanuel Vukovich Yes, absolutely. It’s an early work, composed in 1998. Though written a long time ago, we made some changes, we explored it, and he revised it a bit. Dinuk mentioned that Bartok was a major inspiration in his journey to incorporate elements of traditional or classical Indian…

LSM (VL): … musical culture and tradition. So many common threads, talking about synthesizing seemingly opposing traditions. Of course, the common thread of the environment, sensitivity to nature, conscientiousness of our place in nature, our connectedness with nature, and such. I want to ask you about the many people involved in your project. It’s a multidisciplinary project in a way, certainly with a multimedia aspect in terms of the visual works involved in the beautiful booklet we present. There is a three-dimensional aspect, so it’s not only audio; it’s also visual, including indigenous arts and the work by Mrs. Frank. And there’s a box. Tell me about all of these elements.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Well, I will backtrack for one moment and say that I think connected first to the music is, of course, my two colleagues, and most importantly, Catherine Dowling, who I performed the Sonata with. I just want to say she’s an exquisite pianist, an exquisite musician, and a wonderful human being. I’m very grateful for the opportunity to have recorded this work with her.

Philippe Sly, who’s a very close friend, dear friend. We share a lot of similar values or world views. Philip and I recorded these folk melodies together. He sings and plays the Hurdy-Gurdy. So I want to thank him as well. And then Martha de Francisco, who really is very important both in the repertoire choices and in planning the recording. We spent a week at Domaine Forget in Charlevoix, Sheila came up from New York, and then Catherine joined. So there have been many people involved, including the team at Leaf Music, Jeremy Haruka, the engineer, and Hit Lab Music in Montreal, which released the album, and Warner Music Canada, which distributed it.

But I would say the bigger question of what you were asking… Here, I’ll read this. I found this quote in the middle of the pandemic at some point, and it really stuck with me. “Resilience has been most frequently defined as positive adaptation despite adversity. Recently, however, research has begun to recognize that much of what seems to promote resilience originates outside of the individual. This has led to a search for resilience factors at the individual, family, community, and most recently, cultural levels.” So, during the pandemic, I think many people struggled because the feeling of isolation or separation was very [pervasive throughout]and it’s very difficult; no one is designed to be alone.

[38:24] What Bartok was trying to do, I think at the turn of the century, you had Schoenberg defining the future of music out of the individuality of music within the Western classical music German tradition. They were saying, “We’re going to define the future within the boundaries, structure it, formalize it.” From within. It’s kind of like saying “resilience comes out of me, my own individual identity and strength”. It’s a similar gesture. I think what Bartok was trying to do was being like, “No, no, no. The only way to move forward is to find out how classical music is connected with other forms of music, and how music is connected with other arts

[39:41] LSM (VL): So that connectivity to others, you see, is perhaps embodied in the fact that your project is multidisciplinary.

Emmanuel Vukovich: I would say, that’s the attempt. Yeah, you know, the book in the box came out of the realization that everything today is digital. Basically, albums are digital, and who needs another CD in a digipack? I don’t even have a CD player anymore. Like, I don’t know how to play a CD.

LSM (VL): But you have a gramophone, which is interesting! Going back to a certain extent…

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yeah, we’re going [back]in a certain way. I think LPs will come back, definitely. So I think there is… I can be very honest. I struggle with this as a violinist, which can be a very solitary practice every day alone. And it’s a dream. I’m pursuing a dream, and I believe in that dream. But it’s like, how do we…

LSM (VL): … find our place within a large network?

Emmanuel Vukovich: How can we cultivate resilience?

LSM (VL): Okay, the resilience in a larger context: of other people, community. That seems to me very palpable throughout all the elements, the cohesiveness of your project, through all the elements that you bring together, the text that you wrote so thoughtfully, and that seems to come across.

Emmanuel Vukovich: Well, thank you. I’m very impressed. You’ve really looked at almost everything I’ve sent to you because I’m, you know…

[41.34] LSM (VL): So you wanted to talk about Gubaidulina?

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yes, just last closing thoughts on the projects that I’m embarking on now. One of them is the continuation of the Resilience project, which involves forthcoming albums and getting all this material digitized. The other is that Sheila Silver is going to start writing a new violin concerto for me, that’s going to be called Earth Canticles. And last year, I had the extreme privilege and honor of being introduced to the work and the composer Sofia Gubaidulina. She is 92 now, she’s in Hamburg. She has more or less stopped composing. She has written three violin concertos, the last of which, Dialogue: ich und du (me and you) has never been performed in Canada. I have a bit of a relationship with Yannick Nézet-Séguin, and I’m hoping that the Orchestre Métropolitain might be interested in giving the world premiere of Sheila’s concerto Earth Canticles and Sofia’s third concerto.

She also has a cello concerto written for Rostropovich originally, but it’s called Canticle of the Sun. I will meet her when I go to Europe next month and – I’m assuming she’s going to say no – but my wish would be if Earth Canticles and Canticles of the Sun could both be provided. That would make an amazing album one day. I’m calling it the “Canticles project”, it’s basically these two new violin concertos.

Another project that I just want to mention is… During the pandemic, I did several performances of the solo Bach Partitas and sonatas, and I am now presenting what would be my first recording of these to Warner in immersive audio, Dolby Atmos. What we’ve been playing with – with John Diaz Adams, who’s in Halifax and is one of Canada’s foremost engineers in this – is to explore setting up the recording so that you have the microphone that is picking up more of the bass, behind the violin, the treble comes off here, and the alto-tenor, D and A string would be more here in front so that the listener… Because you have these four-part fugues, and the idea is to bring out the fact that these four-part fugues come from a different direction. You know from their own direction. I mean it’s a little bit theoretical, but the idea is that this immersive audio technology could help bring out the polyphonic aspect of Bach’s music even more. Because this is not a by nature, not a polyphonic instrument.

And then the last project is something that will come from many, many years. It’s called Parsifal and Feirefiz. It’s a collaborative project. It’s about retelling the Grail narrative with West African drumming. These are all projects that, in a sense, speak to the same underlying worldview about, you know, this image that we stumbled across with the roots in the tree. And I think that’s, yeah, OK, done. Yes.

LSM (VL): So just to be clear, Gubaidulina’s concerto, the Canticle of the Sun. was written for cello…

Emmanuel Vukovich: She wrote it for cello, for Rostropovich. I’m going to ask her if she could arrange it for violin. Because then Sheila’s Earth Canticles and Canticle of the Sun would be just a very… she may say no or who knows. I met her official biographer in Basel, Switzerland. […] He’s finishing the biography now and then we want to get it translated into Russian – she doesn’t have a Russian biography to date – French, German, English, over the next few years. I have an appointment to meet with her biographer in February when I’m in Europe, and I’m going to propose the idea to her. I’ve asked Yannick about the third violin concerto and it has yet to be played in Canada. No one has played that yet. That’s.

LSM (VL): I see, I see. So either the third violin concerto…

Emmanuel Vukovich: The third violin concerto definitely…

LSM (VL): But for the recording project, the Canticles, it would be an arrangement of [the cello concerto]. Very good.

Emmanuel Vukovich: You know, I’ll probably end up playing all three eventually, but I just you have to start somewhere.

[47:39] LSM (VL): There is one more thing I wanted to ask you. So if my understanding was the Resilience project was actually designed as a series of albums.

Emmanuel Vukovich Yes, yes. Yeah. Perfect. Perfect. We can, we can.

LSM (VL): So maybe we can finish with kind of a transition…

Emmanuel Vukovich: Yeah, I mean, it didn’t start like that. But as there, you know, as it became clear that there is an enormous amount of material, folk melodies here, and the recordings at Harvard and the manuscripts at Columbia. And then I went to Budapest, I was in Vienna, and I went and had met with the head of the Bartok Archive and Estate in Budapest and spoke with them about it. And then last summer, I was in Turkey, and there’s a big Bartok Museum and Center in Turkey – Bartok spent quite a bit of time in Turkey researching Turkish folk music and North Africa. I believe that this material, as in Bartok’s own words, is a legacy that he’s left behind kind of like Bach’s chorales. Bach’s 400-some chorales have become the foundation of our harmonic language. Every student studies harmony, you know, that’s the foundation. I’m willing to wager that this material here will one day become like Bach’s chorales, the foundation of a new formal language for timbre. That’s my hypothesis.

I think what would be very interesting is to…Well, the first thing that has to happen is all these recordings at Harvard need to be digitized. I mean, they’ve started slowly, but I’ve had talks with the directors of all three institutions. And they’re all interested in collaborating and moving this forward. And so, step one is the digitization of all the recordings, the digitization of all the manuscripts, and then matching up – because there’s a recording for each one. No one has sat down and said, let’s find the recording and line it up. And then looking at how did Bartok interpret this and how would we interpret that today?

And then out of that, I would say: [50:46] work with composers, living composers, and performers to develop new pieces and a language that explores beyond pitch, rhythm, and harmony. All the expressive nuances that performers use and communicate.

I’ll just finish that train of thought. So, the melodies are grouped into ethnic areas, meaning there’s a Turkish collection, there’s a Romanian collection, there’s what he calls the Serbo-Croatian, you know, Yugoslav, which were mostly recorded by Millman Perry, and Bartok only transcribed a fraction of what Millman Perry recorded.

LSM (VL): That’s what I was going to ask you because I understand there’s a recording for every transcription, but is there a transcription for every recording?

Emmanuel Vukovich: No. There are thousands of recordings that have not been transcribed at all. Some of them are maybe, you know, it’s like he’s having conversations with people. It’s not all sung melodies, you know, because he was really researching oral literature tradition.

[52:23] There would be a second album, Bartok in Turkey, let’s say, with the Turkish music, the Romanian music…

LSM (VL): So that’s what I wanted to bring back to the scope of those projects, if we could in a couple of words.

Emmanuel Vukovich: I think in a couple of words, it’s, you know, it would be a multi-album, multi-year project over the next 10 years, maybe 20 – I mean, there’s enough material here for several lifetimes. I had no idea this existed, and I’m sure most of my classical musician colleagues don’t know either. You know, I thought maybe that this was like it was like this much.

You know, all of this here is like a 50th. It’s of room full, it’s boxes and boxes. He spent five years. That’s all he did, basically. I mean, he wrote concerto for orchestra, a viola concerto, the last string quintet… he was writing music, but this was the reason he came to North America. And I want to bring this into the world, into the public awareness because…

LSM (VL): That’s how you see your role perhaps?

Emmanuel Vukovich: I feel like that’s I have a. Yeah, yeah, yeah, and to continue what he started. [53:50] I think and returning to the beginning of our conversation – the tree can only grow tall if it has strong roots. There’s no other way to put it.

LSM (VL): Essentially, it’s about nurturing strong roots. Thank you, Emmanuel, it’s a beautiful way to round off our discussion.

Read:

Biography

Winner of the Fischoff National Chamber Music Competition, Emmanuel Vukovich is the recipient of McGill University’s inaugural Golden Violin Award in 2007, and a three-time recipient of the Canada Council Instrument Bank including a 1690 Nicolò Amati and a 1752 G.B. Guadagnini. His education includes degrees in violin performance from the Juilliard School (Pre-College) with Dorothy DeLay and Masao Kawasaki; McGill University (B.Mus.) with André Roy and Denise Lupien; New England Conservatory (M.Mus.) with Lucy Chapman, Soovin Kim and Donald Weilerstein; and Stony Brook University (D.Mus.) with Philip Setzer and Eugene Drucker of the Emerson Quartet, whose teacher Oskar Shumsky worked with Bartók.